It is always difficult to pinpoint discoveries and inspirations experienced at a major art event. Just as I’m browsing tons of photographs (even though my camera stopped working at some point during my visit to the biennial), more than three weeks after I came back from Venice, I’m realizing how the whole experience is still very much alive and constantly shifting, along with me reading other voices in usual outlets including social media. And between then and now, I’ve also visited Manifesta 14 in Prishtina (to be reported on soon). To continue on the 2022 Venice Art Biennial discoveries track:

Women and conceptual poetry. Yet another thread worth revisiting – and from multiple perspectives, including multimodality of the genre and its complex relationships with the early computer art. Seen through some examples of the artworks by female artists, a very particular materiality of the genre comes to the fore. Among the names to check out I noted Leonora de Barros with her Poema 1979-2014, Mary Ellen Solt, Mirella Bentivoglio and Annalisa Alloatti, Lilliane Lijn with her amazing Poem Machines, Ilse Garnier (in Blason du corps féminin attempting to link a poetic graphic sign with the materiality of female body), and Giovanna Sandiri. By the way, except for Ilse Garnier, none of the names is mentioned at all in existing (and otherwise very informative, insightful and inspiring) histories of electronic poetry which usually ponder the multifaceted and rich genealogies of electronic textuality being traced to concrete poetry. Even when Else Garner is mentioned in one of the fundamental books on early electronic poetry, Prehistoric Digital Poetry. An Archaeology of Forms, 1959-1995 by C. T. Funkhouser, she’s referenced as a part of a duo with her husband, Pierre. This is despite the fact that the name of Mary Ellen Solt features prominently in the anthology Experimental – Visual – Concrete. Avant-Garde Poetry Since the 60s, also as an author of the chapter reminiscing on the history of the genre (M. E. Solt, Concrete Steps to an Anthology In Experimental – Visual – Concrete. Avant-Garde Poetry Since the 60s, eds. K. David Jackson, Eric Vos & Johanna Drucker, Rodopi 1996). Solt has also authored Concrete Poetry. A World View (Indiana University Press 1970) and it is tempting to check her and other female artists’ perspective with the renewed interests in materiality of the digital forms. It seems that it is yet another field, where electronic textuality and new media art are closer than was articulated so far and that such a crossroad still offers a fresh area of research, also from a feminist perspective. It also shows that genealogies of electronic literature that are too narrowly literary may risk omitting important aspects of the development of e-literary forms (which in itself is a very broad discussion, summed up by Roberto Simanowski, among others, in his 2011 book). This is also a note to myself to revise the topic in the nearest future.

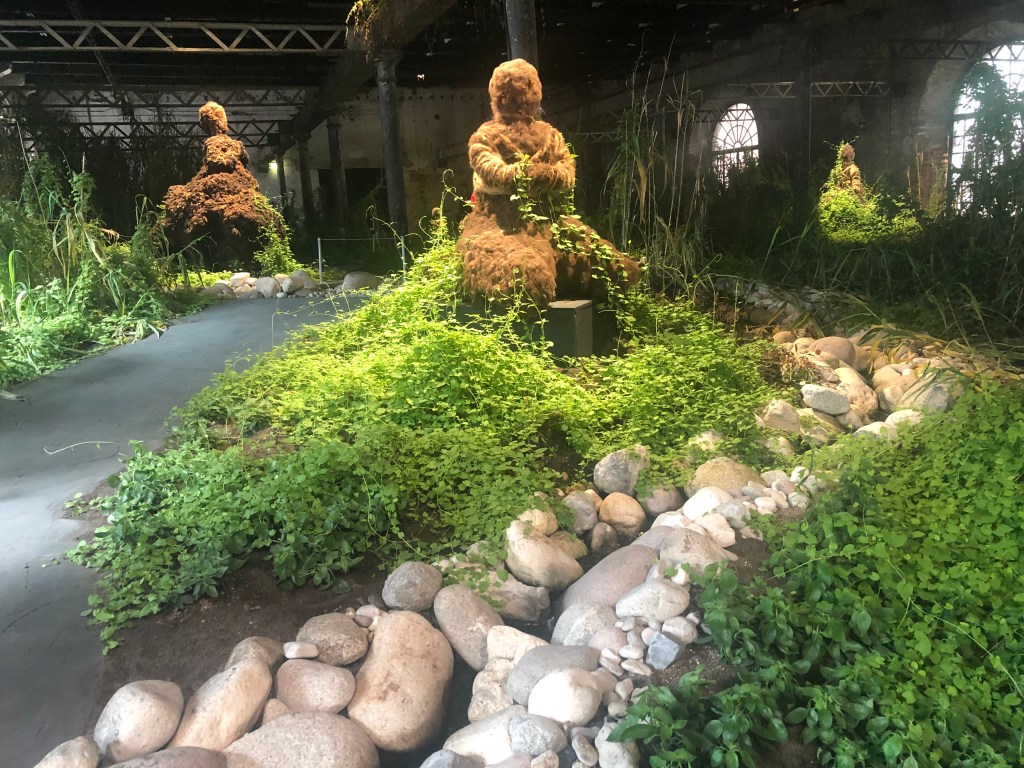

Ecological sensibilities. It is practically impossible to avoid a big elephant in the room: an acute ecological crisis we’re facing. XX-century art has been at the forefront of new environmental sensibilities, as recently reminded by Linda Weintraub among many others. Even listing a sheer number of artworks and projects that thematize ecological turn at this biennial is far beyond the capability of a singular blog post. Zheng Bo presents his new project, Le Sacre du printemps, continuing exploration of queer eco-sexual relationships that we’ve seen in Pteridophilia (I saw it convincingly displayed in the Botanical Garden in Palermo at the Manifesta 12). On the other hand (and in totally different aesthetics) we see anthropocenic landscape paintings of Jessie Homer French, where the convention of figurative realism meets certain dreamlike sensibility in picturing devastating human impact on the environment. Yet, a monumental installation by Precious Okoyomon, To See the Earth before the End of the World, is the most often referred to when it comes to highlighting the ubiquity of environmental art at this year biennial – and deservingly so. For in this vast artwork environmental sensibilities meet reflection on colonialism and colonisation, with all the ambiguity resonating far beyond current crises and bringing up the history of American agriculture, in itself uncomfortably enmeshed in anthropocenic devastation (or maybe constituting its very core). Letting kudzu vine took over a significant part of Arsenale can also be interpreted as a statement of sorts on moral panic surrounding the discourse of invasive plants. As noted by a horticulturalist and botanist, Bill Finch, “The more I investigate, the more I recognize that kudzu’s place in the popular imagination reveals as much about the power of American mythmaking, and the distorted way we see the natural world, as it does about the vine’s threat to the countryside.” And the part of that myth making was so eloquently deconstructed in a brilliant graphic novel that was awarded Robert Coover Award for a Work of Electronic Literature by Electronic Literature Organization in 2021, Leise Hook‘s The Vine and the Fish. A valuable prompt to deconstruct all the moral panic related to so called invasive species (and mostly instigated by the same media that so often to hesitate to adequately represent the massive scale of climate catastrophe), especially considering the genealogy of the concept that can be traced back to Nazi Germany. Certainly, some necessary caution is required, but as Joseph Barla & Christoph Hubatschke remind us in their insightful article, Technoecologies of Borders. Thinking with Borders as Multispecies Matters of Care, “Although current invasion ecology is by no means fascist or xenophobic per se, it has to be noted that the metaphors used to describe alien species, as well as the rhetoric how one has to deal with these species often remains unreflected and therefore problematic. The descriptions of alien species bare uncanny similarities to racist and white supremacist characterisations of refugees.” (Australian Feminist Studies, 2017, 32 (94).

Particular projects. On any major art event of this scale there usually is the whole deluge of names who deserve further research and recognition. One of my major discoveries at the 2022 Venice Art Biennial was Thao Nguyen Phan‘s video work, First Rain, Brise-Soleil (2021-ongoing). The fictional story of Vietnamese-Khmer construction worker, specialising in designing and building brise-soleil, a kind of concrete shades serving as a vernacular ventilation system, is conveyed as a plot intertwined with a folk tale of a durian fruit. Phan’s sensual, slow-paced movie making makes Mekong river a narrative device. It serves as a silent, yet acutely present centrepiece of the story; an agency mobilizing the succession of events and functioning as a material metaphor. I didn’t know it at the time, but roughly three weeks later I would have a chance to see her Becoming Alluvium, an equally beautiful and haunting story, incorporating animations (Phan’s training as a painter shows in this case). In general, more technologically advanced art was rare at this year’s biennial, and it was represented mostly by the section dedicated to the figure of cyborg (granted, revelatory in many regards). Even video art was far less prominent than during recent biennials in 2019 or 2017. But the video works I saw at this biennial, were all touching and inspirational, including both relatively new names and familiar stalwarts. Among the former one could point to a poignant three-channel video installation Chillahona, by a young artist born in Tashkent, Saodat Ismailova, whose earlier video installation, Zukhra, I saw in Venice in 2013. I was reminded of haunting video works by Taus Makhacheva from Dagestan. There seems to be a similar kind of sensibility shared by other video artists from Central Asia, still bearing an ambiguous legacy of Soviet Union – the newest developments in the field get interestingly analysed by Charles Merewhether in his recent book on the topic. Nan Goldin, on the other hand, could hardly be counted as a discovery, yet her Sirens are one of the best video art works I’ve ever seen.

Lagoon. Cruising Venice always means to me a deepening relationship with the city itself and with the Venetian Lagoon; a very special, distinctive environment that could be considered an example of elemental, water-based, large-scale natural computer (on a pair with the one created in 1936 by Vladimir Lukyanov). So Vera Molnár’s Icône 2022 curated by Francesca Franco and located at the New Murano Gallery perfectly activated all the associations that make me think in terms of “vibrant matter” and “mattering” occurring in those ambiguous environments shifting between fluidity and solidity (a recent special issue of Theory, Culture, and Society on Solid Fluidity edited by Tim Ingold and Cristian Simonetti is a good entry point into the topic). Moving between salt / ground / coastline / lagoon / open sea / stable land / islands / temporary islands / wetland is never too obvious, of course if you decide to leave more obvious terrains of La Serenissima and venture into wilder places around. Fusing a creative process of early computer art with the ancient techniques of Murano glassmaking was a brilliant, mind-opening idea. It is in this context, of Venice as a natural computer grounded in an alternative, system-based and sympoietic vision of computing, that Icône 2020 is so massively inspiring. The process is aptly captured in a brief description of the project: “Starting from Molnár first successful computer-based artwork created in 1975 (Computer-Icône/2), which in turn originated from a series of computer plotter drawings made in 1974 (Trapèzes), Icône 2020 for the first time one of Molnár’s key original concepts based on the dichotomy, and subsequent search for balance, between order and disorder, to three dimensions as a sculpture.” And the exposition, displayed in a gallery adjacent to the actual glassmaking workshop, is so beautiful.

All the discoveries and the sheer pleasure of walking for hours in all the main venues filled with art by women, queer and Indigenous artists, did not dimmed, however, some of the more critical thoughts and quite a few doubts raised by the very concept that has been so unequivocally praised. The main line of critique can be boiled down to the sort of escapism that inevitably haunts the exhibition with such a strong focus on the surreal in the world where the most surreal is the massive crisis that shouts from every corner, including on my way to Venice. Additionally, a fair dose of exoticising – willingly or not – Indigenous art and other subjects that usually have been located on the margins of the art world pervades the concept that otherwise is based on noble idea of performative decolonisation. I will ponder both points, however, in the next blog post (probably comparing 2022 Venice Art Biennial with… Manifesta 14, a nomadic European art biennial which this year was organised in Prishtina).