A notice: as a non-native English speaker, I’m always concerned about language issues and do my best to write in proper English. Nevertheless, some irregularities may happen.

-

The Milk (and dry riverbeds) of Dreams, part 2.

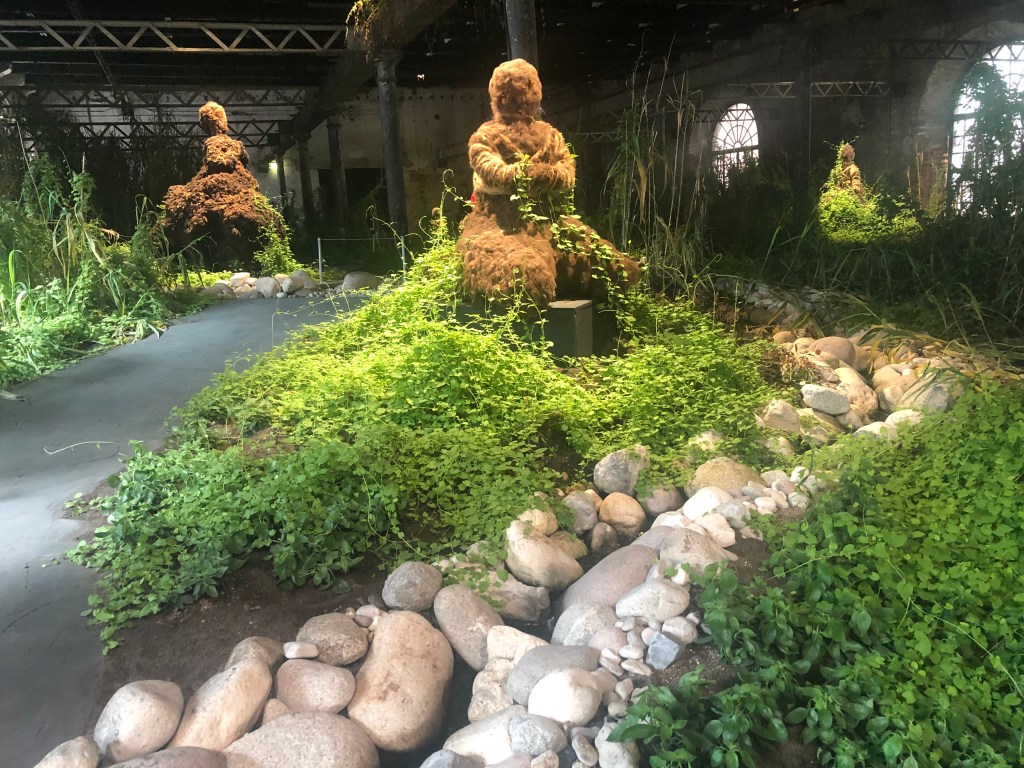

Precious Okoyomon, To See the Earth before the End of the World, exhibition view at the Arsenale. It is always difficult to pinpoint discoveries and inspirations experienced at a major art event. Just as I’m browsing tons of photographs (even though my camera stopped working at some point during my visit to the biennial), more than three weeks after I came back from Venice, I’m realizing how the whole experience is still very much alive and constantly shifting, along with me reading other voices in usual outlets including social media. And between then and now, I’ve also visited Manifesta 14 in Prishtina (to be reported on soon). To continue on the 2022 Venice Art Biennial discoveries track:

Women and conceptual poetry. Yet another thread worth revisiting – and from multiple perspectives, including multimodality of the genre and its complex relationships with the early computer art. Seen through some examples of the artworks by female artists, a very particular materiality of the genre comes to the fore. Among the names to check out I noted Leonora de Barros with her Poema 1979-2014, Mary Ellen Solt, Mirella Bentivoglio and Annalisa Alloatti, Lilliane Lijn with her amazing Poem Machines, Ilse Garnier (in Blason du corps féminin attempting to link a poetic graphic sign with the materiality of female body), and Giovanna Sandiri. By the way, except for Ilse Garnier, none of the names is mentioned at all in existing (and otherwise very informative, insightful and inspiring) histories of electronic poetry which usually ponder the multifaceted and rich genealogies of electronic textuality being traced to concrete poetry. Even when Else Garner is mentioned in one of the fundamental books on early electronic poetry, Prehistoric Digital Poetry. An Archaeology of Forms, 1959-1995 by C. T. Funkhouser, she’s referenced as a part of a duo with her husband, Pierre. This is despite the fact that the name of Mary Ellen Solt features prominently in the anthology Experimental – Visual – Concrete. Avant-Garde Poetry Since the 60s, also as an author of the chapter reminiscing on the history of the genre (M. E. Solt, Concrete Steps to an Anthology In Experimental – Visual – Concrete. Avant-Garde Poetry Since the 60s, eds. K. David Jackson, Eric Vos & Johanna Drucker, Rodopi 1996). Solt has also authored Concrete Poetry. A World View (Indiana University Press 1970) and it is tempting to check her and other female artists’ perspective with the renewed interests in materiality of the digital forms. It seems that it is yet another field, where electronic textuality and new media art are closer than was articulated so far and that such a crossroad still offers a fresh area of research, also from a feminist perspective. It also shows that genealogies of electronic literature that are too narrowly literary may risk omitting important aspects of the development of e-literary forms (which in itself is a very broad discussion, summed up by Roberto Simanowski, among others, in his 2011 book). This is also a note to myself to revise the topic in the nearest future.

Ecological sensibilities. It is practically impossible to avoid a big elephant in the room: an acute ecological crisis we’re facing. XX-century art has been at the forefront of new environmental sensibilities, as recently reminded by Linda Weintraub among many others. Even listing a sheer number of artworks and projects that thematize ecological turn at this biennial is far beyond the capability of a singular blog post. Zheng Bo presents his new project, Le Sacre du printemps, continuing exploration of queer eco-sexual relationships that we’ve seen in Pteridophilia (I saw it convincingly displayed in the Botanical Garden in Palermo at the Manifesta 12). On the other hand (and in totally different aesthetics) we see anthropocenic landscape paintings of Jessie Homer French, where the convention of figurative realism meets certain dreamlike sensibility in picturing devastating human impact on the environment. Yet, a monumental installation by Precious Okoyomon, To See the Earth before the End of the World, is the most often referred to when it comes to highlighting the ubiquity of environmental art at this year biennial – and deservingly so. For in this vast artwork environmental sensibilities meet reflection on colonialism and colonisation, with all the ambiguity resonating far beyond current crises and bringing up the history of American agriculture, in itself uncomfortably enmeshed in anthropocenic devastation (or maybe constituting its very core). Letting kudzu vine took over a significant part of Arsenale can also be interpreted as a statement of sorts on moral panic surrounding the discourse of invasive plants. As noted by a horticulturalist and botanist, Bill Finch, “The more I investigate, the more I recognize that kudzu’s place in the popular imagination reveals as much about the power of American mythmaking, and the distorted way we see the natural world, as it does about the vine’s threat to the countryside.” And the part of that myth making was so eloquently deconstructed in a brilliant graphic novel that was awarded Robert Coover Award for a Work of Electronic Literature by Electronic Literature Organization in 2021, Leise Hook‘s The Vine and the Fish. A valuable prompt to deconstruct all the moral panic related to so called invasive species (and mostly instigated by the same media that so often to hesitate to adequately represent the massive scale of climate catastrophe), especially considering the genealogy of the concept that can be traced back to Nazi Germany. Certainly, some necessary caution is required, but as Joseph Barla & Christoph Hubatschke remind us in their insightful article, Technoecologies of Borders. Thinking with Borders as Multispecies Matters of Care, “Although current invasion ecology is by no means fascist or xenophobic per se, it has to be noted that the metaphors used to describe alien species, as well as the rhetoric how one has to deal with these species often remains unreflected and therefore problematic. The descriptions of alien species bare uncanny similarities to racist and white supremacist characterisations of refugees.” (Australian Feminist Studies, 2017, 32 (94).

At one of the glassmaking workshops in Murano Particular projects. On any major art event of this scale there usually is the whole deluge of names who deserve further research and recognition. One of my major discoveries at the 2022 Venice Art Biennial was Thao Nguyen Phan‘s video work, First Rain, Brise-Soleil (2021-ongoing). The fictional story of Vietnamese-Khmer construction worker, specialising in designing and building brise-soleil, a kind of concrete shades serving as a vernacular ventilation system, is conveyed as a plot intertwined with a folk tale of a durian fruit. Phan’s sensual, slow-paced movie making makes Mekong river a narrative device. It serves as a silent, yet acutely present centrepiece of the story; an agency mobilizing the succession of events and functioning as a material metaphor. I didn’t know it at the time, but roughly three weeks later I would have a chance to see her Becoming Alluvium, an equally beautiful and haunting story, incorporating animations (Phan’s training as a painter shows in this case). In general, more technologically advanced art was rare at this year’s biennial, and it was represented mostly by the section dedicated to the figure of cyborg (granted, revelatory in many regards). Even video art was far less prominent than during recent biennials in 2019 or 2017. But the video works I saw at this biennial, were all touching and inspirational, including both relatively new names and familiar stalwarts. Among the former one could point to a poignant three-channel video installation Chillahona, by a young artist born in Tashkent, Saodat Ismailova, whose earlier video installation, Zukhra, I saw in Venice in 2013. I was reminded of haunting video works by Taus Makhacheva from Dagestan. There seems to be a similar kind of sensibility shared by other video artists from Central Asia, still bearing an ambiguous legacy of Soviet Union – the newest developments in the field get interestingly analysed by Charles Merewhether in his recent book on the topic. Nan Goldin, on the other hand, could hardly be counted as a discovery, yet her Sirens are one of the best video art works I’ve ever seen.

Venice Lagoon. Cruising Venice always means to me a deepening relationship with the city itself and with the Venetian Lagoon; a very special, distinctive environment that could be considered an example of elemental, water-based, large-scale natural computer (on a pair with the one created in 1936 by Vladimir Lukyanov). So Vera Molnár’s Icône 2022 curated by Francesca Franco and located at the New Murano Gallery perfectly activated all the associations that make me think in terms of “vibrant matter” and “mattering” occurring in those ambiguous environments shifting between fluidity and solidity (a recent special issue of Theory, Culture, and Society on Solid Fluidity edited by Tim Ingold and Cristian Simonetti is a good entry point into the topic). Moving between salt / ground / coastline / lagoon / open sea / stable land / islands / temporary islands / wetland is never too obvious, of course if you decide to leave more obvious terrains of La Serenissima and venture into wilder places around. Fusing a creative process of early computer art with the ancient techniques of Murano glassmaking was a brilliant, mind-opening idea. It is in this context, of Venice as a natural computer grounded in an alternative, system-based and sympoietic vision of computing, that Icône 2020 is so massively inspiring. The process is aptly captured in a brief description of the project: “Starting from Molnár first successful computer-based artwork created in 1975 (Computer-Icône/2), which in turn originated from a series of computer plotter drawings made in 1974 (Trapèzes), Icône 2020 for the first time one of Molnár’s key original concepts based on the dichotomy, and subsequent search for balance, between order and disorder, to three dimensions as a sculpture.” And the exposition, displayed in a gallery adjacent to the actual glassmaking workshop, is so beautiful.

Vera Molnár’s Icône 2022

All the discoveries and the sheer pleasure of walking for hours in all the main venues filled with art by women, queer and Indigenous artists, did not dimmed, however, some of the more critical thoughts and quite a few doubts raised by the very concept that has been so unequivocally praised. The main line of critique can be boiled down to the sort of escapism that inevitably haunts the exhibition with such a strong focus on the surreal in the world where the most surreal is the massive crisis that shouts from every corner, including on my way to Venice. Additionally, a fair dose of exoticising – willingly or not – Indigenous art and other subjects that usually have been located on the margins of the art world pervades the concept that otherwise is based on noble idea of performative decolonisation. I will ponder both points, however, in the next blog post (probably comparing 2022 Venice Art Biennial with… Manifesta 14, a nomadic European art biennial which this year was organised in Prishtina).

-

The Milk (and dry riverbeds) of Dreams, part 1.

Somewhere in Venice, photo: M. Styczynski Approaching the airport in Treviso, I already saw the completely melted glaciers in the Alps and had read about severe drought in northern Italy, the worst in 70 years, which emptied out the riverbed of Po. I was also aware of the inevitable irony of the fact that I’m worrying about it sitting on a plane from Kraków to Treviso – a distance which, however, would take at least 2 days to cross for someone like me, who does not possess a private car (and has never possessed it). I was also coming almost straight from our permaculture garden, which proves more resilient to a structural drought we’ve been experiencing in our region for at least the last 7-8 years than the average food producing plots in our area, but where acute imbalances in water management are felt dramatically. I was born and raised in the mountains, and when I compare what I’m seeing around with what I remember from 30 years ago (especially in our mountainous coniferous forests), I’m almost shivering with the whole range of emotions.

Venice Art Biennial like no other

Vera Molnár’s Icône 2022, New Murano Gallery (produced and curated by Francesca Franco) So entering 2022 Venice Art Biennial I was still under impressions left by the images seen from the above and all the news about drought emergency in the basin of the Po river. It certainly has influenced my perception of the massive art exhibition that for the last decade is a staple on my calendar (along with, since recently, Architecture Biennial). The reviews I’ve read were all very favourable, albeit they seemed slightly repetitive in almost univocal appreciation of Cecilia Alemani’s curatorial concept, based on the title of the book by Leonora Carrington and venturing into the phantasmagoric and magical world of imagination, as conveyed by the broadly defined surrealism. This year, however, I wanted to appreciate both the city (so dear to anyone who looks for the alternatives to a car-based culture) and the lagoon (to me Venice is never separate from the lagoon), and the biennial itself. Not an easy feat though, considering how massive the event usually is and how tempting the wild beaches on the Isola di Pellestrina proved to be in the past.

One of the most precious lessons that covid taught me is: take it easy and don’t rush. I was late on a bandwagon, having succumbed to it a couple of weeks ago for the full 7 days when I was completely unable to do anything else than just completely give in. So this year’s Art Biennial experience was radically different – rather than striving to see as much as I was able, I was picking and choosing (which is why I didn’t see neither one of other stellar shows on a display at the time: Anish Kapoor at Gallerie di Academia and Pallazzo Manfrin nor Anselm Kiefer at Palazzo Ducale. The latter presented considerable scheduling challenges, being displayed at THE Venice landmark venue and I was visiting during a peak season. Luckily, I’ve already seen a major (and really captivating) Bruce Nauman’s retrospective at Punta Della Dogana while visiting for the Architecture Biennial in 2021. Neither was I aiming at visiting all the national pavilions in Giardini or Arsenale. I also closely monitored any signs of being mentally, cognitively or emotionally exhausted, even though I must at the same admit that I often seek to enter this special, trance-like state of mind induced by experiencing the art for 7-8 hours a day, a couple of days in a row. But this year my energy resources seemed depleted and fragile.

I’m offering such a broad context for my draft impressions below to better ground my particular perspective, far from seemingly univocal appreciation and delight. I couldn’t escape a considerable doubts in regard to the curatorial concept offered in the times of major upheavals, social and ecological disasters, all the trauma brought by almost 3 years of the pandemic and almost half a year of Russian aggression that spilled over to other countries of the region, where we feel all the dread of the cruelty of war on a daily basis, with every post in a numerous Facebook groups asking for help and support to Ukrainian war refugees (more than 2 million in Poland). Is seeking the (safe) heaven in the imaginary a proper gesture in such challenging times? Does it really offer relief or does it rather taste like an ultimate act of major hypocrisy of the artworld? I couldn’t shake off similar questions popping now and then, while I was coursing the Biennial premises.

And I don’t have any clear answers. For being able to walk for hours among artworks produced by overwhelmingly women-identifying artists was such a treat in itself; especially when seeing the latest (and last) works by a late Portuguese artist Paula Rego, who didn’t live to see her contribution. Her series Seven Deadly Sins (2019) is particularly touching in the times when women’s reproductive rights seem to be under constant attack on a daily basis, pretty much everywhere in the world. The combination of the pandemic, Brexit, and flight cancellations barred me from seeing her major retrospective at Tate Britain last year. An artist whose series of 10 paintings, Untitled: The Abortion Panels (July 1998 – February 1999), is credited with influencing the public opinion in Portugal to the extent that legalizing abortion became possible. After the referendum in 2007 had decided on liberalisation of abortion law, women’s reproductive rights have been finally secured in Portugal. So it is within such a broader context that I see Rego’s dark and at times even grotesque imagery as a sign of hope – much needed these days when women’s rights (especially the right to safe abortion) are under assault worldwide and on a daily basis.

I would like to start nevertheless with all the delights, inspirations and pleasures of venturing into the area of “fortuitous finds”, to borrow the phrase from Siegfried Zielinski’s Deep Time of the Media. For 2022 Venice Art Biennial has demonstrated how much of a creative potential could have been wasted, if it wasn’t for so many efforts to bring to spotlight works and activities that at the time of their production were either considered not art, or located at the margins of the artworld (not surprisingly, overwhelming majority of those cases were / are women, LGBTQ+, and indigenous artists – and it’s worth keeping in mind that all those categories should be seen as arbitrary, unstable and contested). Even if such a perspective generates some problems in itself (and I’ll write about it next) and may result in exoticisation of the margins, delving into multitude of global imagination liberated from the established lines of interpretation of what constitutes the work of art is very refreshing and beneficial.

I brought a notebook full of handwritten notes on the particular artists I would like to continue to discover for myself, but here I’m going to focus on some broader tendencies, perspective shifts or narrative threads that proved to be generative and inspire further research.

Discoveries

Vera Molnár’s Icône 2022, New Murano Gallery (produced and curated by Francesca Franco) Discovery no. 1

The confluence of pre-digital art and textile art. By no means a new topic, especially after the seminal retrospective of Anni Albers at the Tate Modern in 2018-2019. Here it constituted a visible thread running through entire exhibition and offering a very interesting and fresh feminist perspective on both the history of computer art and all the ambiguities of post-digital repositioning of the material and the computable. If you add the observation that textile work is a significant part of Indigenous art in many places of the world, shift in the perspective gets even deeper and more generative of follow-up research. It still gets further problematized by the fact that, for example, in Sámi art the category of duodji (very roughly, equivalent of Western crafts) does not fall into a binary division separating art and craftsmanship, instituted by the European modern art (more on the history of this division: Carolyn Korsmeyer, Gender and Aesthetics. An Introduction, New York: Routledge, 2004). It is wonderfully demonstrated by a Sámi artist, Britta Marakatt-Labba, whose intricate, hauntingly beautiful embroided landscapes are on display in the main pavilion in Giardini. Textile work is also often a form of activism: both to Marakatt-Labba, (whose works I’ve seen for the first time in a gallery in one of the Swedish Sapmi’s town’s galleries – either Gallivare, or Kiruna – around 2012 and have become impressed ever since) and to Charlotte Johannesson, an autodidact textile artist, a programmer and a digital art pioneer, who together with her husband, Sture Johannesson established in 1966 a gallery called Cannabis and in the 80s the platform for early experiments with the digital technology, Digitalteatern (Digital Theatre). Britta Marakatt-Labba-Labba belongs to a generation of Sami activists who protested against the hydropower plant by Alta River in the 1970s and she interestingly sums up her work as “embroidering resistance art”. The theme of weaving can be also found (albeit more implicitly) in Akosua Adoma Owusu’s video art, Kwaku Ananse. A Ghanaian-American cinematographer and producer presents a female protagonist in search of her deceased’s father spirit. In the process, she also finds out how weaving the new knowledge patterns based on the old layers of memory is crucial for the ability to move forward. Granted, there are also the more obvious examples, such as Rosemarie Trockel’s automated “knitting-machines”, and equally obvious larger thematic clusters, such as the whole section dedicated to the figure of cyborg, but the confluence outlined here has really captivated may attention and I am going to expand it at some point into a longer and fully developed writing. There are also embroideries that incorporate troubled and messed up materiality of storytelling, such as Violetta Parra‘s arpilleras, but here again I’m making a note to myself to do more research around a Chilean artist / singer-songwriter and her artworks.

…to be continued.

-

Switching gears

The end of academic year is traditionally the time, when I suffer (not surprising). The suffering is related to my own assessment of where did most of my energy go over the last 10 months. Yes, yet another year is passing by when I promised to myself to write more, to research more, and to dedicate more time to my students. That was around the end of September of 2021, when it seemed we’re freshly (almost) out of the pandemic. The pandemic years seem to have coagulated into one, long and greyish stretch of time filled with butt-, spine- and eye-hurt instigated by the endless Zoom or MS Teams meetings and bureaucratic nightmare of equally endless chain of paperwork following the pattern: print-sign up-scan-email. Occasionally, I had a chance to engage in collaboration that brought about a few satisfying projects. I paid a lot of attention to be regularly present in my permacultural garden and continue herbalist passion that I started a few years ago.

So I’m trying to switch gears as much as possible, and this website is yet another attempt at keeping me disciplined about some of my own promises. To remember when I’m getting angry and disillusioned with the structure of academia, preying on my life energy and effectively turning me into zombie.

June 28th, Cancer New Moon, late afternoon, after a mild thunderstorm which alleviated a bit the severe drought that has been devastating this mountainous region in Central Europe for the last couple of years. I’m starting yet another blog, curious where it is going to lead me.